Avoiding double taxation when you emigrate: a practical checklist

Contents

hide

The Ultimate Guide on Leaving the Collapsing Western World

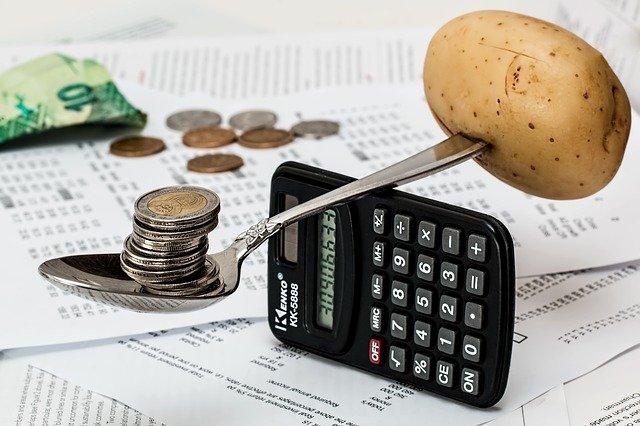

You know what’s worse than paying taxes? Paying taxes twice. That’s what happens when you pack up and move abroad but forget that both your old country and your new one think you owe them. One paycheck, two hungry governments. It’s not fun, and it’s not rare either.

The good news is, you can mostly avoid it if you’re organized. Doesn’t mean it’s painless, but there’s a checklist you can run through before you hop on that plane.

Let’s walk through it. No suits, no legal jargon, just practical stuff that’ll save you from the “oh crap” moment later.

This sounds dramatic, but some countries don’t let you go. The U.S. is notorious: you can live in Timbuktu and they’ll still make you file. Eritrea does the same, though you probably don’t know anyone moving there.

Most countries? They’ll cut you loose once you prove you’ve really left. But until you know how your passport country works, don’t assume you’re free.

So step one: figure out if your home country taxes you because you live there or because you’re a citizen. If it’s the second, buckle up—you’ll be filing forever, even if you owe zero.

A lot of people think moving abroad is as simple as booking a flight. As long as you have location independent income, that’s true … but not for the taxman. He’s like that clingy ex who won’t accept you’ve moved on.

They look at things like: do you still have a house? Family there? Bank accounts? Gym membership? If too many ties remain, they might still call you a “resident” for tax purposes. Which means, yep, double taxation.

So the checklist here is boring but essential: close what you don’t need, move bills and subscriptions to your new country, and get that official “non-resident” status if your country offers it.

This is where treaties save your skin. Loads of countries sign “double taxation agreements” that basically say, “Hey, we won’t both hit this person for the same income.” If one country taxes it, the other either exempts it or gives you a credit.

Sounds simple, but the devil’s in the details. For instance, pensions might be taxed in your new home, but dividends might be taxed back home.

It’s a mix. Which means your homework is: look up if there’s a treaty, and actually read the section about your income type. Salaries, rental, investments, they all get treated differently.

Even without a treaty, some governments throw you a bone. The U.S. has the Foreign Earned Income Exclusion, which basically says you can earn up to a certain amount abroad and not pay U.S. tax on it.

Or you can use the foreign tax credit: whatever you paid abroad can offset what you owe at home.

Other countries have their own versions of this. The point: before you panic, check if your home country has credits, deductions, or exclusions you qualify for. Sometimes the system does (accidentally) work in your favor – apart from the fact that all taxes are legalized theft.

Now flip the coin. Your new country has its own definition of when you’re “theirs.” Some go by the classic 183 days a year. Others have fuzzier rules like “center of vital interests.”

Basically: if your spouse, house, or job is there, congratulations, you’re a resident, even if you spent fewer days.

So checklist item: know when you cross the line into tax residency in your new country. It matters, because the day you qualify, the bills start arriving.

Here’s a sneaky one. Even if you’re doing everything right, your home country might demand you report every foreign bank account.

Not necessarily to tax it, but just to know. For Americans, it’s FBAR and FATCA forms. Miss them, and the penalties are brutal, even if you owe zero.

Checklist item: find out if your country requires foreign account reporting. Keep track of balances. Boring, yes. Necessary, also yes.

Don’t treat all income the same. Salary, freelance earnings, pensions, rental income, stock dividends, each one can be taxed in a different way by different governments.

For example, rental income is usually taxed where the property is, not where you live. That might be good, might be bad, but you need to know.

Do yourself a favor: write down every stream of income you expect to have and check how it’s taxed in both places. No surprises later.

This is the golden ticket. Once you’re officially living somewhere, go get that “certificate of tax residency.”

It’s usually a piece of paper from the tax office that says you’re one of theirs. When your old country comes sniffing, you can wave it around like a shield. Without it, you’re just saying “trust me, I live there now,” which doesn’t fly.

One of the biggest mistakes is skipping returns because you assume you owe zero. The problem? Tax offices don’t read minds.

If you don’t file, they might assume the worst and send bills anyway. Filing a zero return is like saying, “Look, I did the homework. Nothing to see here.” Keeps things clean.

Nobody wants to spend money on accountants, but here’s the truth: a one-hour session with someone who actually knows cross-border taxes can save you thousands.

You don’t need them forever, just enough to point you in the right direction. Think of it as paying for a map before heading into the jungle.

Avoiding double taxation isn’t glamorous. There’s no magic trick, no hack. It’s just a checklist you run through: know your home country’s rules, know your new country’s rules, see if there’s a treaty, grab the credits you can, keep proof, and don’t slack on paperwork.

Once you’ve done all that, you can stop worrying about two tax bills and get back to why you moved abroad in the first place: sun, freedom, maybe cheaper rent, maybe just adventure. Whatever your reason, it’s definitely not to fund two governments at once.

Every year, glossy expat magazines and relocation blogs roll out a familiar headline: “The World’s Cheapest Places to Live in” And every year, the same destinations reappear as if nothing…

Most people follow a script so narrow it barely qualifies as a life. They are born in a particular place, raised there, go to school nearby, find work in the…

Everyone starts the same way: scrolling through listings in some sunny coastal town, seeing prices that look like Monopoly money compared to back home, and thinking, “Why not?” Then you…